|

Hilbre

Bird Observatory - Half A Century of Bird Ringing and Recording

by Bob Anderson and Steve Williams

The tidal Hilbre islands consist of some six hectares of land and rock in

the Dee estuary, about 1km from the nearest point of the mainland at Red

Rocks. Their location in the rich feeding grounds of the estuary make them

important as a roost site for waders. Hilbre itself is the largest of the

group, at something less than five hectares; most of its surface consists

of rough grassland and some bare rock, but a cluster of buildings of

various ages occupies the lower, east side of the island. Their associated

(private) gardens and paddocks provide shelter for passerine migrants. The

main island’s position at the extreme north-west point of Wirral means

that, along with the peninsula’s north shore, it affords opportunities for

seawatching not otherwise found in Cheshire.

The islands have long attracted attention from naturalists, with records

of society visits going back to the nineteenth century. In the first half

of the twentieth century a succession of well-known Wirral and Cheshire

writers (e.g. Coward, Boyd and Ellison) visited Hilbre, while the

opportunities for wader photography were exploited first by Farrar and

later by Hosking and others. Drawing upon these sources, and the

increasing number of records available from local societies and

individuals, Ellison and Craggs (1) produced a checklist of the birds of

the islands in 1955. Hilbre was therefore already a well-known and

well-recorded site even before the inception of the Bird Observatory.

Nevertheless, a group of local birders who were already visiting the

islands regularly felt that more could be learned by systematic

observation and ringing, and the Observatory came into being early in

1957. The annual report produced that year was the first of an unbroken

sequence extending to the present day (2). It should be said that, from

the start, the interest was not wholly in birds but in all aspects of the

islands’ natural history: for example, there is a fifty-year sequence of

counts of the Grey Seal population, while light trapping of moths is a

more recent development. This is reflected in the comprehensive volume on

Hilbre edited by Craggs in 1982 (3) and in the annual reports, but such

activities are beyond the scope of the present paper.

The Observatory

The main movers in the creation of the Hilbre Bird Observatory (HiBO) were

John Gittins, a dynamic West Kirby man with a long association with the

island, and Professor J D Craggs, who was already ringing House Sparrows

Passer domesticus on Hilbre as part of his long-term study of the small

colony then resident there. Fuller appreciations of the work and character

of these two memorable and much-loved personalities can be found in

obituary notices in CAWOS Bird News (4) and HiBO reports (2-1999 and

2-2001). They were joined by seven other founder members, four of whom

were products of the then flourishing Birkenhead School Natural History

Society, and over the next few years a succession of Wirral-based birders

and ringers was added to the membership.

Birding in 1957 was very different from today, and more localised. The

leisure market had yet to take off; equipment was more basic; information

was much more limited; travel was far more restricted, and expensive.

Ringing probably represented a more exciting option for young birders than

it does in 2007. The beginnings of the Hilbre Bird Observatory have to be

seen in this context. The primary motivation of the founder members was to

learn more about the birds passing through the island and the waders

feeding around its shores, but there was also the attraction of

contributing to wider knowledge. The network of major observatories was,

by now, established; a case was recognised (notably by Kenneth Williamson

at the British Trust for Ornithology, who offered early encouragement to

Hilbre) for smaller “mini-observatories” to supplement information by

filling the geographical gaps in the network.

The two key developments which enabled the Observatory to take off in 1957

were permission to construct a small Heligoland trap in one of the

gardens, and the use of a tiny hut in the grounds of one of the holiday

bungalows for overnight accommodation and as a base for ringing

activities. The original Heligoland site is still in use, though the trap

has been rebuilt several times, and subsequently two further Heligolands

were constructed in the east-side paddocks. In 1962 Hoylake UDC,

recognising the value of the group’s work, provided a rather larger hut

just north of the Canoe Club; though the building has now gone, its

enclosed garden still provides a mist-netting site. In 1989 HiBO was

fortunate to obtain, thanks to the previous occupants, the Dixon family,

the tenancy of the southernmost bungalow on the island which continues to

provide reasonably comfortable accommodation – far removed from the

original 6’x4’ garden shed.

Hilbre Bird Observatory buildings: 1957-1962 (right) and 1989 to present

day (left) (Steve Williams)

Possession of a permanent base led to improved coverage. HiBO members will

normally be present on most weekends, with added effort (early morning

visits and full-time residence on the island) at peak migration periods.

Typically, the island will now be visited for ringing or recording

purposes by members on 250 or more days in the year.

Ringing Activity

Despite the time and expense involved in their maintenance, the Heligoland

traps remain a mainstay of ringing at Hilbre. They are sited in the

limited cover available on the island, and are effective on an exposed

site even when weather conditions limit mist net use. They are

supplemented, for passerine trapping, by mist nets and some small wire

(Potter) traps. Early wader ringing involved S-traps, clap-nets and

dazzle-netting (the last a somewhat hazardous activity, utilising Aldis

lamps and wet-cell batteries on slippery rocks) before the advent of

rocket nets to catch roosting waders. The latter led to a brief period of

relatively large wader catches, but the practice was discontinued in the

1970s. Before the organisation of the Dee Estuary Voluntary Wardens the

roosting flocks at the mouth of the estuary were subject to serious

disturbance by various public activities; the Dee became known as an

“aerial roost” (the birds spending the tide in the air), and HiBO

concluded that cannon netting on the islands would not help this

situation. Limited wader ringing continues, primarily using mist nets but

only at night.

It was always accepted that (waders briefly apart) Hilbre would never

produce large ringing totals: a presentation on the HiBO’s work at the

North-West Ringers’ Conference in March 2007 took as its theme the

statement that “size isn’t everything” - that even a small site could

contribute something to ornithological knowledge.

However, since 1957, HiBO has ringed over 32,000 birds (excluding early

rocket netting of Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus which involved

several thousand birds) of almost 100 species, but this modest total

includes some useful results.

Of these 32,000 birds the pie chart below indicates that a very high

proportion, almost 88%, is of passerines.

Figure 1

(left): Pie chart showing percentage of passerines, waders and other

species ringed by HiBO 1957-2006. Figure 1

(left): Pie chart showing percentage of passerines, waders and other

species ringed by HiBO 1957-2006.

Willow Warbler Phylloscopus trochilus is clearly the dominant passerine

species with over 10,000 now ringed at Hilbre (representing about 1% of

those ringed by the BTO), and is interesting on a number of counts.

The numbers illustrate how ringing expanded knowledge of the birds of an

already well-watched site: in 1957 it was known that a few could be seen

frequenting the gardens, but nobody then guessed that fifty, sixty or a

hundred individuals could be present, and ringed, in a single day.

Moreover, bearing in mind its size and overall totals, Hilbre punches

above its weight when compared with the national average for recoveries of

many of the species ringed at Hilbre and this includes the Willow Warbler.

Not surprisingly, HiBO members have taken a particular interest in

patterns of Willow Warbler movements.

Figure 2 (right): Map indicating some of the British recoveries and controls of

Willow Warblers obtained by HiBO.

The pattern of recoveries and controls from HiBO is interesting; we have

had a number of recoveries/controls from Scotland and Northern Ireland.

This has led us to believe that the majority of Willow Warblers passing

through Hilbre (particularly in August) are from these breeding areas and,

to a lesser extent, northern England. This is emphasised by birds ringed

in these areas during the breeding season and then captured on Hilbre

during the August return migration or in some instances the following

spring.

There is also evidence to suggest that birds use the same west coast

migration routes with several recoveries/controls each from Portland,

Bardsey and Calf of Man Bird Observatories, including birds ringed and

captured in subsequent springs. However, interestingly, we have only had

one from the east coast (ringed at Holme Bird Observatory in Norfolk on 12

May 1969 and controlled at Hilbre on 8 May 1970). We have several examples

of Willow Warblers that have presumably overshot their intended

destinations as they have been ringed on Hilbre (for example, one bird on

20 April 1988) and subsequently controlled further south (e.g. the same

bird retrapped on Bardsey three days later on 23 April 1988).

There are also several foreign recoveries and/or controls of Willow

Warblers and these have helped add to the ‘bigger picture’ that the BTO is

compiling. A couple of examples are a bird ringed in Switzerland on 9

April 1980 and caught on Hilbre six days later, another ringed in Belgium

on 23 April 1987 and captured at Hilbre on its return south on 17 August

1989 and one ringed at Hilbre on 12 September 2002 and captured in

southern Spain on 6 October 2002. This latter bird was captured at a

traditional feed-up area and was probably its last stop before it made its

trans-Saharan crossing.

Weather patterns have also been closely studied at Hilbre by HiBO and here

are two weather charts which indicate the classic fall conditions required

for the arrival of large numbers of Willow Warblers (and other species are

involved in much smaller numbers) at Hilbre in spring (figure 3) and

autumn (figure 4).

Figure 3

(left): Classic spring weather conditions for a large fall of passerines

on Hilbre. Figure 3

(left): Classic spring weather conditions for a large fall of passerines

on Hilbre.

The chart for spring (figure 3 left) shows high pressure centred over

North Africa and the Iberian peninsula moving north-eastwards. This

produces south-easterly winds off the Continent. A front moving north to

south arrives at Hilbre after dawn producing cloud cover and/or rain which

downs lots of nocturnal migrants (typically involving Willow Warblers).

The autumn chart (figure 4 below) is taken from the largest fall of Willow

Warblers to ever occur on Hilbre (5 August 2006) when high pressure north

of and over Scotland produces ideal conditions for birds to leave their

breeding grounds (clear skies and light winds) and a north-easterly airstream. A front moving west to east

across the Irish Sea arrives at

Hilbre at dawn ‘grounding’ literally hundreds of Willow Warblers. For more

detailed analysis of the autumn chart readers are referred to CAWOS Bird

News (5). across the Irish Sea arrives at

Hilbre at dawn ‘grounding’ literally hundreds of Willow Warblers. For more

detailed analysis of the autumn chart readers are referred to CAWOS Bird

News (5).

Figure 4

(left): Classic autumn weather conditions for a large fall of passerines

on Hilbre.

Other birds, though ringed in smaller numbers, have added to local

knowledge and/or produced interesting recoveries. Grasshopper Warbler

Locustella naevia is a good example. A species not recorded at Hilbre

prior to the establishment of the Bird Observatory in 1957, a remarkable

225 birds have been ringed at Hilbre in the 50 years since. This

represents just over 1% of Grasshopper Warblers ringed in the UK during

that time and the recovery in Scotland of a Hilbre-ringed bird was an

early reward for our work in 1963.

Grasshopper Warbler

Locustella naevia

(right), 225 have been ringed on Hilbre

1957-2006 (Steve Williams). Grasshopper Warbler

Locustella naevia

(right), 225 have been ringed on Hilbre

1957-2006 (Steve Williams).

So far as waders go, attention has always been concentrated on Purple

Sandpipers Calidris maritima - a speciality of the island, though sadly

reduced in numbers in recent years (e.g. a maximum of only 29 birds during

2006, against a peak of over 70 in the 1960s). Colour ringing demonstrated

the return of individuals year after year, and in 1964 a bird ringed at

Hilbre five years earlier was shot (allegedly by an Eskimo hunter) in

Greenland. This was something that encouraged HiBO members for many years,

being the first overseas recovery of a British-ringed Purple Sandpiper and

early evidence of the origins of our wintering west coast birds.

Turnstone

Arenaria interpres

(left), one of many colour ringed on Hilbre over the

last decade

(Steve Williams). Turnstone

Arenaria interpres

(left), one of many colour ringed on Hilbre over the

last decade

(Steve Williams).

Similarly, with our colour ringing of Turnstones Arenaria interpres we

have had a number of birds seen or captured on passage in Iceland as well

as numerous sightings of our birds around the west coast of Britain.

Clearly, there is not enough space to celebrate the ringing achievements

of HiBO despite its size. These are just a few illustrations that suggest

that the Observatory has succeeded, as a ringing station, in terms of its

original ambitions. Additionally, the founders’ hopes for the occasional

rarity have been met over the years, and several species have been added

to the county list. These are discussed further in the next section.

Figure 5: Sample of interesting recoveries/controls from HiBO ringing

efforts 1957-2006

Records and Observations

A crude but significant measure of the Observatory’s contribution to

knowledge of Cheshire’s birds is that in 1957 the total number of species

recorded on Hilbre stood at 157; by the end of 2006 it had risen to 260

(this on an island which had been well watched, and in the opinion of one

noted county ornithologist, speaking not long after HiBO was established,

was “over-watched”). The current figure includes an impressive list of

rarities and/or birds new to the county, some of which might not have been

discovered had it not been for the ringing effort.

Some of the more interesting examples include the first Cheshire and

Wirral Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus on 13 October

1973 – Hilbre has since had seven more records of this delightful, once

much sought after, rarity. 2007's fine male Subalpine Warbler Sylvia cantillans was the second for Hilbre but

only the fourth for Cheshire and Wirral. Two each of Melodious Hippolais

polyglotta and Icterine Warblers Hippolais icterina, the latter species

occurring twice on Hilbre in spring (1970 and 1973), were rare events on

the west coast and constituted the first and second records for Cheshire

and Wirral. Other good passerines have included two Woodchat Shrikes

Lanius senator (of five county records), Pallas’s Warbler Phylloscopus

proregulus, Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata, and Red-rumped Swallow

Hirundo

daurica (all third county records).

One of the most incredible records for Hilbre was probably the

Yellow-breasted Bunting Emberiza aureola on 7 September 1994. Very much a

Shetland speciality, this was one of the first west coast mainland

records. Obviously, seabirds are also emphasised with the first county

records of Great Shearwater Puffinus gravis (October 1971) and Cory’s

Shearwater Calonectris diomedea (August 1980). Other notable species

include Laughing Gull Larus atricilla, two White-winged Black Terns

Chlidonias leucopterus and Collared Pratincole Glareola pratincola

(another first record for the county).

The rarities apart, regular observation has led to improved knowledge of

frequency of occurrence, and/or fluctuation in numbers of all species that

occur on or around the Hilbre islands group.

Many examples of species’ status that have changed considerably in the

time that HiBO has been running are from a positive perspective – Storm

Petrel Hyrdobates pelagicus, Brent Goose Branta hrota/bernicla,

Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus, Osprey Pandion haliaetus, Marsh Harrier

Circus aeruginosus, Little Egret Egretta garzetta, Long-tailed Skua

Stercorarius longicaudus and Little Gull Larus minutus. Some of these are

simply as a result of the species increasing within and/or expanding their

range but other reasons, such as better identification awareness (e.g.

Long-tailed Skua) and observer awareness of when and where to look (e.g.

Storm Petrel and Little Gull) may also have played a part.

Figure 6 below indicates the dramatic rise in numbers of Pale-bellied

Brent Geese Branta hrota at Hilbre in the last decade or so. Prior to the

early 1990s Pale-bellied Brent Goose was very scarce at Hilbre but before

this Dark-bellied Brent Goose Branta bernicla was the more regular of

these two closely related species.

Figure 6: Peak counts of Pale-bellied Brent Geese at Hilbre from winter

1995/96 to 2006/07.

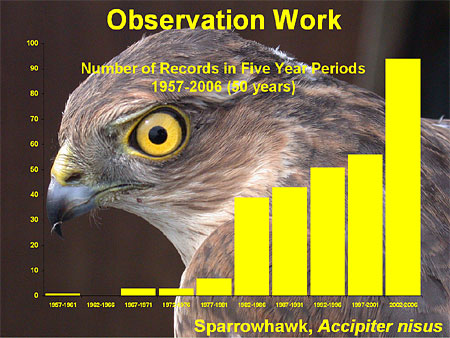

Similarly, figure 7 below indicates the dramatic increase in Sparrowhawk

records at Hilbre in the last 50 years (shown in five-year periods). It

has had a particularly significant increase since the early 1980s,

mirroring its general recovery on the mainland.

Figure 7: Number of Sparrowhawk records at Hilbre in five-year periods

1957-2006 (50 years)

Those species that have been affected with a downward turn in recent times

sadly include two of our favourite species, namely Willow Warbler and

Purple Sandpiper. The former has seen a decline nationally and the latter

has seen numbers dwindle in the last few winters. The reasons for the

Purple Sandpiper decline are possibly partly due to more movement between

wintering sites in north Wirral (with better feeding habitat available at

Wallasey and Leasowe), but more likely that birds are staying further

north in winter, although this latter suggestion is yet to be proved.

Seawatching has always attracted birders to Hilbre, and no seabird more

than Leach’s Petrel Oceanodroma leucorhoa – adopted as the symbol for

CAWOS as well as HiBO. Long associated with autumn north-westerly gales

there is perhaps no better place on the ‘mainland’ of Britain to watch

this enigmatic petrel, in terms of location, ambience and views of the

birds themselves (but of course we are biased!). However, all of the other

important seabird sightings and counting that HiBO carries out should not

be passed over. Hilbre, and HiBO in particular, is particularly

significant in county terms for providing data for divers, grebes,

shearwaters, sea-ducks, gulls, terns and auks (as well as waders and

passerines as already discussed above).

The limited land area of the islands makes it relatively easy to study,

and ring, the limited population of resident birds. The House Sparrow

colony which attracted Craggs, and was the subject of two papers by him

(6), (7) was largely dependent on livestock foodstuff, and disappeared

many years ago. However, a number of passerine species breed on the

islands, and are studied through five-year cycles using territory mapping

methods. Of particular interest are the flourishing Linnet Carduelis

cannabina colony (the subject of an ongoing study) and Wren Troglodytes

troglodytes (the island having once been regarded as unsuitable breeding

habitat). Additionally, about 15 pairs of Shelduck Tadorna tadorna now

breed – a significant increase from the two or three pairs to be found

when the Observatory began, and consistent with changes elsewhere in the

county.

The observation work carried out by HiBO is not restricted to the daily

log of species and numbers and the ringing efforts, but also includes

provision of data to CAWOS and other organisations, the Winter Gull

Survey, Wetland Bird Survey, Breeding Bird Survey, Brent Goose Survey,

CAWOS Wintering and Breeding Atlas surveys and the BTO Atlas survey work

planned to commence in the winter of 2007.

Conclusion

Has it worked out as the founder members hoped, and has it been

worthwhile? This brief account of fifty years’ work on the islands

suggests that the answer to both questions should be in the affirmative.

The twin aims of finding out more about the birds using the islands and

making a contribution, however modest, to wider ornithological knowledge,

have been achieved. As changes take place over the years, there are always

new questions to answer, and new trends to be identified. There seems no

need to stop work, and no reason to lose interest, even after half a

century. Fortunately, the Observatory is better housed, better equipped

and perhaps most significantly, better manned and covered than it has ever

been – we are looking forward, with eager anticipation, to what the next

fifty years might produce.

Bob Anderson and Steve Williams

References:

(1) Craggs J D & Ellison N F (1955), The Birds of Hilbre Islands,

Cheshire, Northwest Naturalist

(2) Hilbre Bird Observatory (1957-2006), Hilbre Bird Observatory Report,

HiBO

(3) Craggs J D, Ed (1982), Hilbre – The Cheshire Island, Liverpool

University Press

(4) Anderson R (2002) Bird News No 53, CAWOS

(5) Williams S (2004), Bird News No 64, CAWOS

(6) Craggs J D (1967) Bird Study volume 14, pp53-60

(7) Craggs J D (1976) Ibid volume 23, pp 281-284

Acknowledgements:

Many thanks are due to Chris Williams for providing data on ringing,

recoveries and controls and also to Pete Williams for commenting on an

early draft and reviewing the final draft of this article.

Editor: this article first

appeared in the Cheshire and Wirral Bird Report 2007 and appears here with

the kind permission of the Editors and Authors.

Top of

page

January

Bird News

|

|

Cattle Egret at Neston, Jan 8th 2008,

Steve Round ©

The Christmas

period saw an influx of Cattle Egrets into the country, at least 30, and

one of these duly turned up here. Although news only reached birders on

the 3rd apparently it had been present on farmland next to the A540 near

Neston at least a week before that. This

is the second record for Wirral. It, or possibly a second bird, was seen

on Burton Marsh on 25th and 26th. The

following day a Great White Egret was observed flying inland at the same

site at dusk, and was relocated off Neston

Reed Bed on the 30th.

A look at the

Brent Geese graph in the above article (figure 6)

demonstrates the dramatic rise in numbers of these birds on the Dee

Estuary since the winter of 99/00. Well, they are still increasing in

number with a remarkable 172 counted on a flat calm sea off

Little Eye on 12th. These are mostly of

the pale-bellied race, the main population winter in Ireland and

apparently a record number of 29,500 were present at Strangford Lough

(near Belfast) in October 2007 with 30% young, so this population is

obviously doing very well. Pink-footed Geese are another species doing

well. We sometimes get large movements over the estuary with birds moving

from Norfolk to Lancashire, max count this month was 500 on 14th over

West Kirby. But we also have an

over-wintering flock on the marshes, this flock seems to be increasing

slowly each year and max count was 320 on the 25th giving good views from

Parkgate and Neston, they seem to be very

active at high tide flying off the edge of the marsh. Whooper Swan is

another bird which is increasing, the 61 counted on

Shotwick Fields on the 1st is almost

certainly a record high count for that site. Other wildfowl of note was a

first winter male Long-tailed Duck seen off

Hilbre on several days at the start of the month, up to 450 Pintail

spent most low tides in the channel off

Thurstaston and at least 300 Common Scoters were off

Point of Ayr on 26th, no doubt just a very

small portion of the total Liverpool Bay flock.

Purple Sandpiper bravely coping with sea spray

on rocks below the Lifeguard Station,

Wallasey Shore, Jan 25th 2008, Matt Thomas ©

A mainly mild and windy month meant low numbers of waders, although 2,100

Black-tailed Godwits and six Spotted Redshanks at the

Connah's Quay Reserve are not bad

numbers. We've also had reasonable numbers of Purple Sandpipers with at

least 40 on Hilbre, 11 on rocks by the

Wallasey Lifeguard Station and seven on

a platform on New Brighton Marine Lake

at high tide. There seems to have been loads of Oystercatchers around

although I haven't seen any total counts for the estuary, but we've had

good numbers roosting on West Kirby Shore

nearly every high tide ever since they returned from breeding in late

summer, 6,000 was max this month. We've still got some overwintering

Greenshank with singles seen at Heswall,

Gilroy Nature Park and West Kirby Marine

Lake, with two at Connah's Quay.

The same windy

weather which suppressed wader counts brought in a pale phase Arctic Skua

off West Kirby on 24th, I think this

is the first ever Jan record for Wirral although we have had several

December records in the past. There have been both Marsh Harriers and Hen

Harriers of Burton,

Heswall and

Parkgate, usually only single birds have been noted but there were two

Marsh Harriers off Burton on 2nd and

Parkgate the following day, and two Hen

Harriers off Neston Reedbed on 19th. At

least three Peregrines and two Merlins were regularly observed through the

month. Up to four Short-eared Owls have been on the marshes and there have

been some good views of Barn Owls at dusk at

Burton.

Two Snow Buntings

took up residence on Little Eye towards

the end of the month, with singles briefly at

West Kirby and

Hilbre. 15 Brambling were at

Connah's Quay on 21st and 25 Twite was

the max seen at Flint Castle. Cormorant

numbers continue to increase, one day at

West Kirby we counted a total of well over 1,000 on

Bird Rock,

Little Eye and flying south down the estuary.

What to expect in February

Brent Geese numbers will still be high at the beginning

of the month, in some winters they peak in February although it would be

remarkable if we increased on January's figures! February is also the

month when Common Scoters peak in Liverpool Bay, most will be

further west but we can still get good numbers with 3,000 counted off

Point of

Ayr last year. Look out also for the much rarer Velvet Scoter. Other

wildfowl should include Gadwall at the Connah's Quay

Reserve, 22 were here

last Feb. Also at Connah's Quay should be several Spotted Redshanks, they

particularly like the Bunded Pool.

Apart from Oystercatchers numbers of waders have been

well down this winter, but a cold still spell over several days should see

Knot and Dunlin numbers rocket. A still day would also be ideal conditions

to see Great Crested Grebes off North Wirral, a record 458 were counted

last Feb.

Unfortunately no big high tides are due this month, the

max height being just 9.7m, we would need a strong westerly gale to bring

that over the marsh at Parkgate. However, a visit to the car park at

Heswall Riverbank Road should be rewarding, the tide covers the marsh at

much lower heights here than Parkgate. We should get good views of

Short-eared Owls, and probably Water Rails and Hen and/or Marsh Harriers as

well as the usual waders and ducks.

Many thanks go

to Richard Steel, Steve Liston, Neil McLaren,

Jimmy Meadows, Matt Thomas, Andrew Wallbank, Paul Vautrinot, Roger Morgan,

Mike Cocking, Tony Twemlow, John Kirkland, Pete Hilton, John Ferguson, David Haigh,

Mike Hart, John Jakeman, Henerz Cook, Iain Douglas, Graham Thompson, Allan Conlin,

Dave Wild, Graham Jones, Steve Round, Steve Williams,

Dave Edwards, Chris Butterworth, Jane Turner, Charles Farnell, Paul Shenton,

David Small, Gilbert Bolton, Steve Ainsworth, Damian Waters, David

Thompson, Mark Gibson, Alec Thomasson, Colin Schofield, Allan Hewitt, John Tubb,

Dave Harrington, Paul Roberts, Norman Hallas, Phil Woollen,

Phil Liston, Colin Davies, Jason Stannage, Bernard Machin,

Michael Clarkson, Mike Jones, Peter Poole, Nigel Young, James Smith, Rob

Black, Ian Bedford, Steve Hassell, Bryan Joy, Steve Roberts, Richard

Graham, Bernard East, Peter Poole, Graham Mercer, the Dee Estuary Voluntary

Wardens and

the Hilbre Bird Observatory

for their sightings during December. All sightings are gratefully

received.

Top of page |