Dee Estuary Birding

Monthly Newsletter...

February 2025

Newsletter

Species Spotlight - Sanderling

"Sanderlings are only

normally found at the tide edge on sandy shores, for this is the little

bird that follows each wave in and out like a clockwork toy, picking

small shrimps from the water. At low water they sometimes feed on tiny

molluscs and at high tide they may search along the strand line of

seaweed for sandhoppers and small flies."

Birds in Cheshire and Wirral (Atlas)

(Ref1).

These are the first two sentences in the Sanderling description in that landmark publication (The Cheshire and Wirral Atlas) and, as it was as good as anything I could write, I decided just to quote it!

It was Allan Conlin's count 0f 1,475 Sanderlings at

Hoylake in November, the highest there since 2013, which got me

thinking about this small wader. Other than a general impression that

numbers have recently been increasing here, I realised I didn't really

know a great deal about them. So this article brings the current status

of Sanderlings locally up to date as well as summarising the work which

has been ongoing internationally, particularly over the past 20 years,

to try and better understand their movements along the East Atlantic

Flyway.

Dee Estuary and North Wirral

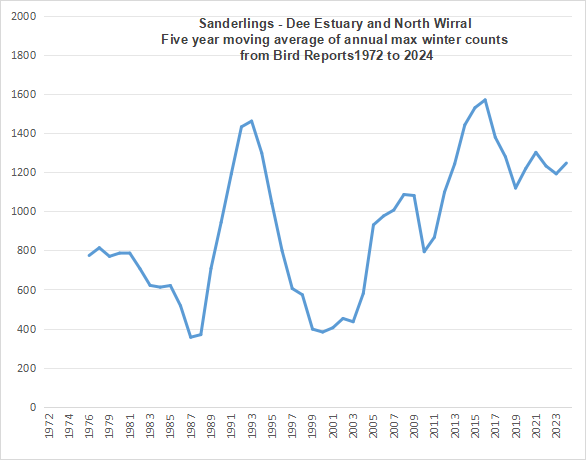

As far as Sanderlings on the Dee Estuary are concerned, the year can be split into three - autumn migration (July to September), over-wintering (October to March) and spring migration (April to June). Historically, numbers spending the winter here were much lower than the large migrating flocks. Hedley Bell (Ref 2), writing in the early 1960s, said that counts in winter were never more than 50 and often considerably less. Regular counts started in 1970 (mainly Webs [Wetland Bird Survey] but also ad hoc counts started to be regularly reported in the Bird Reports) and these winter counts show a definite, if somewhat irregular, trend upwards - as the graph below shows:

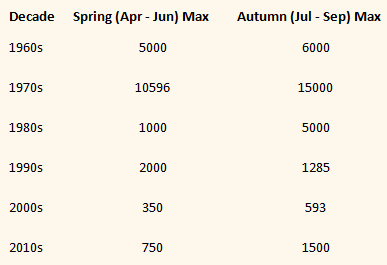

There was a time when the Dee Estuary, together with

Morecambe Bay, had the highest counts in the country during the

migration periods. These migrating flocks reached peak numbers in the

year of 1973/74 when 15,000 were recorded in both the autumn and the

following spring with Gronant holding the biggest numbers. Similar

numbers were recorded in Morecambe Bay at a time when the whole of the

Wash held less than 2,000. The table shows the maximum counts during

each migration period for each decade as reported in the Bird Reports.

The numbers of Sanderlings counted migrating through

our area differs wildly from year to year, particularly in spring. The

drop off in numbers in the 1980s was actually greater than is apparent

in the above table with only nine years between 1981 and 2000 when the

max spring count was greater than 100. More recently, these spring

counts have become more regular and since 2012 the max count has always

been greater than 100, and the latest figures show a five year average

of

355 for max spring counts. Although there was a similar drop off in

autumn counts during the 1980s numbers have usually been both higher

and more regular than in spring. Flocks can pass through quickly,

though, and 1983 was an interesting example and I quote from the

1983 Cheshire Bird Report "An extermely high count was received of 5000

at

Red Rocks on Aug 9th; the observer had recorded 400 the previous day".

More recently the five year average was 424 for max autumn counts (2019

to 2023).

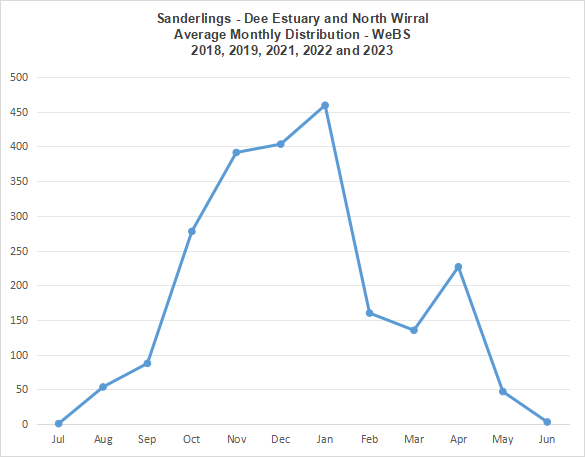

The monthly distribution shown above (2020 not included because of lockdown) shows that numbers peak in winter as recorded by WeBS. These once a month WeBS counts probably underestimate numbers during migration as there will be a high turnover of birds and larger flocks may only be present for a day or two before moving on. For example, in April 2023 a good sized flock of 420 were at Hoylake on the 18th, but only 140 were present two days later for the WeBS count.

Liverpool Bay

The Liverpool Bay estuaries are on the north-west

edge of the Sanderlings' non-breeding range and lie directly on their

migration route to Iceland and onwards to Greenland - they are thus

vitally important stop-over sites for them to feed up before crossing

the Atlantic, and for their return after breeding. Their relatively

mild martime climate also means they are important as a mid-winter

refuge during freezing weather on the European continent.

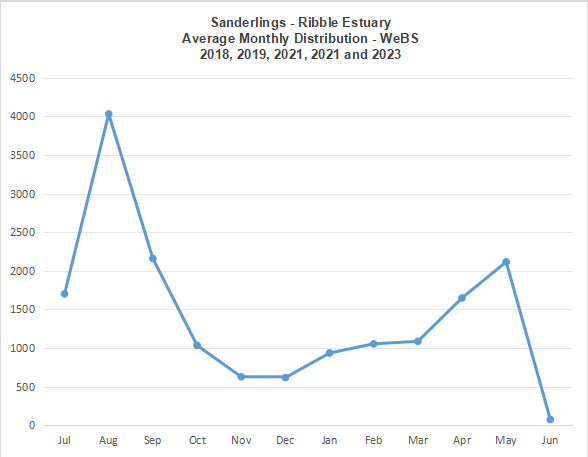

The Ribble has thousands of Sanderlings present

during migration and the monthly distribution is almost the opposite of

that on the Dee, although the Ribble winter minimum in December is

still higher than our mid-winter maximum! For Sanderlings it seems that

the vast stretches of sand on the Ribble estuary is particularly

attractive to them. The highest count in recent years was 8,000 in

August 2015. Intiguingly, the monthly distributions for the mud loving

Knots and Dunlins also show peaks in spring and autumn on the Ribble,

and in winter on the Dee estuary (Ref 3), so I'm not quite sure what it

is about the Ribble that is so attractive to migrating waders.

The stretch of coast between Ainsdale in the north

and Seaforth in the south, including Formby and Crosby shores, (WeBS

rather misleadingly call this large area the 'Alt Estuary') is another

important area for migrating Sanderlings although the contrast between

the migrating periods and winter is far less pronounced. For example,

in 2022 numbers peaked in August with 1515 whereas in 2023 they peaked

in December with 988. Colour ringing shows there is much interchange of

birds between this stretch of coast and the north Wirral coast and it

seems likely that there is an over-wintering flock which uses the whole

area to feed and roost in.

Morecambe Bay holds the record for the second ever highest WeBS count of Sanderlings in the UK. This was in May 1974 when 15,200 were counted. There were several other five-figure counts in the early 1970s then, for unknown reasons, numbers just crashed and for 1975/76 the maximum count was only 65! Numbers remained very low and the next count greater than 1,000 wasn't until May 1986 when there were just over 4,000. Probably there were problems with counter coverage during the migration periods, although tens of thousands of Dunlins, Knots and Oystercathers were being counted in winter over those same years. Whatever happened numbers never recovered and for the 24 years between 1986 and 2010 max counts were above 1,000 only 10 times. Over the past five years the highest count was 2,953 in May 2019, but the most remarkable figure was the max count in 2022/23 when 885 Sanderlings were counted in June 2023. Obviously very late migrants feeding up before flying to the high Arctic to breed - maybe they had come all the way from South Africa.

It's always good to see the juveniles arriving in August and September knowing that just a few weeks earlier they were just tiny

balls of fluff in Greenland. Some years Jeroen Reneerkens has asked us to determine the juv/adult ratio in order to estimate

how successful the breeding season has been.

UK Status

In the UK Sanderlings have been increasing since the start of WeBS in 1970, with the five year average currently about double it was back in 1974/75.

Numbers in the UK peak in August and then decline to about half that through the winter. The spring peak is vary variable but usually only slightly higher than winter counts. The winter population is around 20,000 (Ref 4) which includes an estimate of birds found on the coast away from estuaries and therefore not covered by WeBS. Of our regular wintering estuarine birds Sanderlings have the smallest population, compare that 20,000 with the estimates for Dunlin, 340,000, and for Knot, 260,000.

Currently the Wash has the biggest numbers in the

UK, and there was a massive 17,374 Sanderlings counted there in August

2019, the five year average (2022/23) on the Wash is 10,720. The second

most

important site is the Ribble estuary followed by the Alt estuary,

Morecambe Bay, Thames estuary and Carmarthen Bay, with the Dee estuary

in seventh place.

Migration

I've mentioned migration several times already in this article, but where exactly are our Sanderlings migrating to and migrating from?

If you'd asked that question a few years ago you

would have got some very vague answers like "It's assumed that......",

"We think that.....", "...not fully understood...", ...information is

not yet available...", "the origins and movements of the different

populations are still not clear....". Perceived wisdom had it that the

birds breeding in Greenland passed through the UK and spent the winter

in West Africa whereas our wintering population were all birds that

breed in Siberia and Svalbard. In addition the Sanderlings which winter

as far south as South Africa where also thought to be part of the

Siberian breeding population, and the Greenland birds didn't go

beyond west Africa. Sanderlings also breed in north-east Canada and it

was just not known whether any of these crossed the Atlantic with the

Greenland birds or all headed south towards South America. The

situation is complicated with waves of Sanderlings coming through -

some flying straight through the UK after feeding up, some stop to

moult and then fly on whilst others stay several weeks before moving

on, and then we have the over-wintering birds.

to Reykjavik International Airport in May 2009. Between 2009 and 2016 it has been recorded 56 times

on the same beach in Iceland, 21 times at Hoylake and Meols, twice on Formby Beach and once at Ainsdale.

Which nicely demonstrates how site faithful they are. Photo by Roy Lowry at Meols.

To try and clarify all this Jeroen Reneerkens set up a Sanderling colour-ringing scheme in 2006, with birds to be initially ringed in Greenland, Iceland, the Netherlands, Mauritania and Ghana. Covering such a large area with a large number of birds to ring, this was a big undertaking. Jeroen had to organise ringing teams in different countries together with all the different coloured rings, and equipment for catching the birds, plus ensuing that all the paperwork was carried out properly. Then he had to rely on people to observe and report the colour-ringed birds - people like you and me, citizen science in action - and lastly find the resources and people to subsequently analyse and write up the results (Refs 5 and 6). On the Dee estuary we've been only too pleased to help the recording of these birds and in my database we have 76 records of 25 colour-ringed Sanderling, these included birds which were ringed in all the countries mentioned above. I know many more colour-ringed Sanderling have been recorded elsewhere in Liverpool Bay, especially along the Sefton coast.

This work continues but we can now say that the

birds that breed in Greenland distribute themselves all the way from

Scotland to southern Africa. Many stay in north-west Europe for the

winter with many also in West Africa, but some end up all the way in

southern Africa. The south-west of Iceland has been confirmed as a

major staging area. Colour ringing has shown that at least some birds

which breed in north-east Canada join the Greenland birds in Europe and

Africa (Ref 6).

However, the birds that breed in Siberia remain something of a mystery. We know some certainly use the East Atlantic Flyway but exactly where and in what proportion remains unknown, but the indication is that numbers are relatively small. There has been some interesting observations on the eastern end of the Wadden Sea in Denmark of Sanderlings heading north in spring. They noted that the Sanderlings flew either WNW/NW or ENE/NE, with no intermediate directions observed. The proportion heading easterly towards Siberia was 14%, significant but obviously a lot lower than the 86% heading towards Iceland/Greenland (Ref 7). Remember this is the eastern end of the Waddensea where, presumably, any Siberian breeding Sanderling will concentrate.

So Jeroen, and everyone else involved in his project, still has plenty of work to do.

References and Other Sources of Information

For the Dee Estuary I have used the data in the Cheshire and Wirral Bird Reports (1964 to present day), Clwyd/North-east Wales Bird Reports (1972 to present day), Wetland Bird Survey counts and records from sightings published on this website (www.deeestuary.co.uk). For the Ribble Estuary, Alt Estuary and Morecambe Bay I have used data published in the Lancashire Bird Reports (2018 to 2023), and also Wetland Bird Survey counts.

As well as the books referenced below numerous on-line articles have been read, mostly (co-)authored by Jeroen Reneerkens. I have referenced the most important ones below but I would recommend going to Google Scholar and searching for 'Sanderling migration' to get a more comprehensive list.

References

1. David Norman (editor), Birds in Cheshire and Wirral (Breeding and Wintering Atlas), Liverpool Univerity Press, 2008.

2. T. Hedley Bell, The birds of Cheshire, 1962.

3. Richard Smith, NW Estuaries - Knot and Dunlin, Dee

Estuary Birding July 2010 Newsletter.

4. Population estimates of wintering waterbirds in Great Britain, March 2019, British Birds Vol. 112.

5. Jeroen Reneerkens & Edward Koomson, Migration routes of Sanderling: insights after a year of colour-ringing, Global Flyway Network: progress report for 2007.

6. Jeroen Reneerkens, Demographic monitoring along the East-Atlantic Flyway: a case study on Sanderling using international citizen science, East Atlantic Flyway Assessment 2020, Wetlands International/BirdLife International.

7. Kim Fisher & Hans Meltofte, Departure directions of Sanderlings and 'tundra' Common Ringed Plovers from the northernmost Danish Wadden Sea in spring, Wader Study 122(1), 2015.

Richard Smith

The plumage, particularly on the head, is different to the one shown at the top of this article, maybe this is a second year bird - but apparently there can be quite a lot of variation in breeding plumage

Colour Ring Report

Turnstone

Blue - White flag (AA)

Ringed on Hilbre on 30/3/2024.

Recorded on Hilbre 30/01/2025.

This was the first sighting of this bird since it was ringed last year.

It was the first one ringed with a new scheme, we

look forward to seeing more.

Knots

January was another good month for spotting

ringed and flagged Knots and we had a total of 258 records at Meols,

Thurstaston, Hoylake and West Kirby. Here is a sample of some of the

knots we've seen over the past few months which show some interesting

movements.

Yellow flag (94N)

A lot of

the Knots which spend the non-breeding period on the Liverpool Bay

coast stage on the west coast of Iceland in May on their way to

north-east Canada to breed. In 2017 they managed to catch and ring

several hundred at a coastal farm called Skogarnes just to the south of

the

Snaefellsnes peninsula. Yellow flag 94N was one of these birds.

We saw it at Thurstaston the following December and it stayed in the

area until early March 2018. It was back at Skogarnes the following

May, and also in May in both 2023 and 2024, showing how site faithful

they are. It's been recorded most winters on the Dee estuary since 2018

(except for 2021/22), and it's only record away from either the Dee

estuary or Skogarnes was at Formby in December 2018.

Y8PPYG

Ringed on Griend (an uninhabited island in the Dutch Waddensea) in

November 2021, as a juvenile.

As a non-breeding second year bird it spent the following summer in the

Waddensea being seen on the islands of Ameland and Terchelling. The

following winter it was recorded once at Heysham on Morecambe Bay, then

in May 2023 it was in west Iceland.

It came back from breeding via the Wadensea (in September) then flew

west to Dublin Bay where it was recorded several times in November

2023. It then flew east again to the Dee Estuary where we had our first

sighting of it at Thurstaston in January 2024. Although it wasn't

recorded in Iceland in 2024 it came back again via the Waddensea after

breeding being seen at Griend (it's ringing location) before ending up

at Meols in January 2025.

Oflag(79P)/G

Ringed

at Ainsdale in May 2024 this was one of several thousand second year

birds which spent the summer at Leasowe and Seaforth.

After summer many of these second year birds dispersed away from

Liverpool Bay, some flew east to the Waddensea, but this one decided to

head to southern Ireland, being recorded at Dungarvan, Wexford, in

October 2024 and at Clonakilty (west of Cork), in January 2025. Of the

birds recorded on the Dee Estuary/north Wirral this is only the second

one to be found on the southern coast of Ireland.

Oflag(27E)/G

This bird has been ringed twice. It was fitted with Orange flag LEU in

January 2020 at Dublin Bay.

The following summer it was at Ainsdale after returning from breeding,

and back in Dublin Bay in early 2021. In March 2022 it was a part of a

catch at Ainsdale, and, because the original flag showed some wear, it

was fitted with a new orange flag - 27E.

Since then it has been showing some interesting movements being

recorded in Iceland in May 2022 and 2023, as well as Formby and

Heysham.

Our first sighting of it came at Meols on 20/11/2024 and just over a

week later it was at Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland, on 1/12/2024.

This interchange between the east coast of Ireland and Liverpool Bay

seems to happen quite frequently and we've seen birds which have flown

in both directions at least once during the winter.

Ringed at Ainsdale in March 2022 it was recorded at both Meols and

Thurstaston in the winter of 2023/24. In March 2024 it decided to do

something different and flew all the way east to the small island of

Sylt in the German Waddensea, just south of the Danish border. As well

as Iceland, some birds stage on the northern tip of Norway in May, so

maybe that is what it was going to do. Whatever it was doing, it was

back at Meols early December 2024.

'Photographic Guide

to

Colour-marked Red Knot' - download the PDF file by clicking here.

Colour Rings were recorded by Richard

Smith, Stephen

Hinde, Tony Ormond, Matt Thomas, Colin Schofield, Steve Williams, Alan

Hitchmough and David Leeming.

Richard Smith

January Bird News

A Little Stint continues to over-winter and was seen several times at

both Hoylake and Meols. Other waders included at least 10,000 Knots

giving spectacular views at Meols with birds both roosting and feeding,

often a few feet from the promenade. On Hilbre there was a good count

of 27 Purple Sandpipers on the 12th and Heswall had an exellent

count of 660 Bar-tailed Godwits and 237 Golden Plovers on the 26th.

During some calm weather at least 14 Red-throated

Divers were on the sea off Hoylake on the 16th and 430 Great Crested

Grebes the following day off Meols and Leasowe.

Although often somewhat elusive, this Black Redstart, first seen on the

9th, was a very showy bird at Fort Perch on New Brighton - lots of

photos were taken! At Neston Sewage Works a Siberian Chiffchaff arrived

on the 11th and stayed a few days, and over at Flint at least 20 Twite

were on the marshes.

What to expect in February

We've had some really big spring tides in February over the past few

years bringing spectacular views of Hen and Marsh Harriers, Short-eared

Owls, wildfowl and waders - particularly at Parkgate and Burton. This

year I'm not sure if the tides are going to be high enough to reach the

wall at Parkgate although Heswall Riverbank Road should be good.

Pink-footed Geese increase this month as they leave Norfolk, and last

February there was a record count of 23,816. Many feed on the marshes

and get flushed on these high tides making for a fantastic sight and

sound. Note that there are some very high tides predicted for the first

three days of March, so that should be good.

There will be signs of spring and on any mild day

woodpeckers will be drumming in the woods and our woodland and garden

birds will be singing. There will even be some early spring migrants

with the first Avocets arriving at Burton Mere Wetlands, and a passage

of Stonechats is often seen in February along the north Wirral coast.

Out to sea we often see Little Gulls, they won't be actually migrating

yet but often increase in number prior to flying north east in March

and April. Depending

on the weather and wind direction we might even get a very early Sand

Martin or White Wagtail.

February Highest

Tides:

1st 13.02hrs (GMT) 9.8m

2nd 13.43hrs (GMT) 9.8m

28th 11.20hrs (GMT) 9.7m

Note: 10m tides on March 1st, 2nd and 3rd.